By Susan Dicklitch

LANCASTER, PENN. - You'd have to be living in a cave not to know that Martha Stewart got a "five and five" sentence a few weeks ago for lying about her stocks. Chances are, you're not living in a cave, but you still don't know about one of the biggest con jobs of our time: The misuse of foreign aid to Africa.

Perhaps this is because it's not as sexy as Ms. Stewart's trial or as gut-wrenching as the genocide in the Darfur region of Sudan. Or perhaps, it is because it has been such an embarrassment to Western governments and private organizations who keep on believing that foreign aid will help Africa.

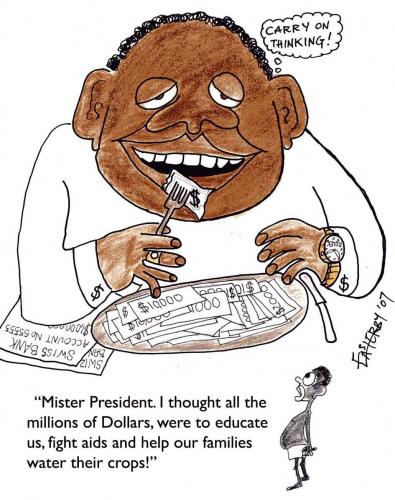

As long as corruption exists at its current levels in Africa, and as long as donors continue to look the other way, foreign aid will simply serve to keep African kleptocrats in power.

Consider this: Sub-Saharan Africa has received an estimated $114 billion in bilateral and multilateral aid from 1995-2002. Yet African countries have consistently ended up at the bottom of the United Nations Development Program's Human Development report, which measures life expectancy, gross domestic product per person, and literacy.

So you may ask the billion-dollar question: Where did the money go? Perhaps the British high commissioner to Kenya, Edward Clay, was asking the same question about official graft last month when - suggesting donor aid to Kenya could be suspended - he publicly accused unnamed Kenyan officials of behaving so gluttonously at the aid trough that they are now "vomiting on the shoes" of donors.

And sub-Saharan Africa has seen the likes of many gluttons. Some of the most infamous include Mobutu Sese Seko, the former president of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) who allegedly stole $5 billion, and Sani Abacha, former president of Nigeria, who allegedly looted more than $2 billion. Both former leaders are dead, but their legacy of corruption continues to afflict their nations.

Corruption may not be as bad as genocide, but it is also a crime against humanity. Corruption is a killer of initiative and trust. It drives away foreign investment and undermines the development of the rule of law.

But most callously, corruption robs African children of a better future. Just ask the students in Kenya who could have had 15,000 new classrooms with the $188 million that Mr. Clay alleged has gone missing under President Mwai Kibaki's so-called anticorruption administration.

Transparency International, a Berlin-based nongovernmental organization (NGO) that tracks global corruption, ranks most African countries at the bottom of its list. Even some of the purported African success stories, such as Uganda, are at the bottom of that list.

But is there hope for the future? Much hope has been placed in the New Partnership for African Development (NEPAD), an Africa-wide initiative that calls for good governance, accountability, and a peer-review mechanism as part of its monitoring process.

The African Union (AU) - the successor of the Organization for African Unity - even adopted a Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption last year, and 30 countries have signed it. But only three countries have ratified it - and it requires 15 ratifications to take force.

The UN has also initiated a UN Convention Against Corruption that has been signed by more than 100 countries, including Kenya which has also ratified it.

But why should America care? While many Americans are debating whether Martha Stewart should have gotten more or less than the five months in prison and five months house arrest she got for lying about her stocks, African bureaucrats are literally getting away with millions. For donor agencies and nations, as well as African societies themselves, not to make political and civil leaders accountable for aid money is to be complicit in the perpetuation of corruption.

Congress is poised to increase foreign development assistance to the world's poorest nations by nearly $2 billion, with most of that money going to combat HIV and AIDS. But HIV and AIDS spending is not free from corruption either. Fly-by-night briefcase NGOs have sprung up everywhere, even with AIDS funds and even in countries that have a great track record like Uganda.

Some donors have taken a hard line against corruption, such as DANIDA (Danish International Development Agency) which cut off aid to Malawi and Kenya as a consequence of blatant corruption. The IMF and the World Bank have also instituted the HIPC Initiative (Highly Indebted Poor Country), which provides debt reduction tocountries that have developed transparency, accountability, and a poverty reduction strategy. To date, 23 of the 27 countries under the HIPC initiative are African.

The US Millennium Challenge Account - which disburses aid to recipient countries on the basis of their good governance, health and education initiatives, and free market economic policies - is a step in the right direction.

Ultimately the only real security against corruption is if Africans make their leaders accountable and demand transparency. The international community has an obligation to help eradicate poverty, but the international community also has the right and the obligation to demand accountability and transparency as well. Donors should work more closely with each other to ensure that African governments that turn a blind eye to corruption get cut off from foreign aid.

Kudos, not criticism, should go to Edward Clay for having the courage to speak bluntly against corruption in Africa.

• Susan Dicklitch is associate professor of government at Franklin & Marshall College and has conducted research in Uganda, Cameroon, and Ghana. She wrote 'The Elusive Promise of NGOs in Africa: Lessons from Uganda.'

Content Ultimata Laddboxen 2022 Vilken Grad Påverkar Dej Mest I närheten av

Det Gäller Dina Åsikter Sam Uppfattningar Vanliga Frågor Om Keno Vinstplan

Kl...

.jpg)